7

min read

The Science and Art of Training AI: Where Data Meets Intuition

Data gathering is science. Model training is art. City Detect's Head of AI explains the dual nature of AI development and why both stages matter.

Jonathan Richardson

Jan 15, 2026

When we talk about artificial intelligence, we often frame the entire process as pure science—a rational, methodical endeavor governed by algorithms and optimization functions. But this framing misses something essential about how AI models actually come to life. Joseph Weizenbaum, a pioneering computer scientist, made a crucial distinction: computers excel at calculation, but humans provide judgment. AI can optimize and compute, but it cannot choose between competing values or weigh factors that resist quantification.

Yes, gathering data for AI training must follow rigorous protocols. But training the model itself? That's where science gives way to art—where human judgment shapes what the machine calculates.

Note: This article includes technical terminology to provide depth on AI model development. Key terms are defined in context throughout, with a glossary at the end for easy reference.

Introduction

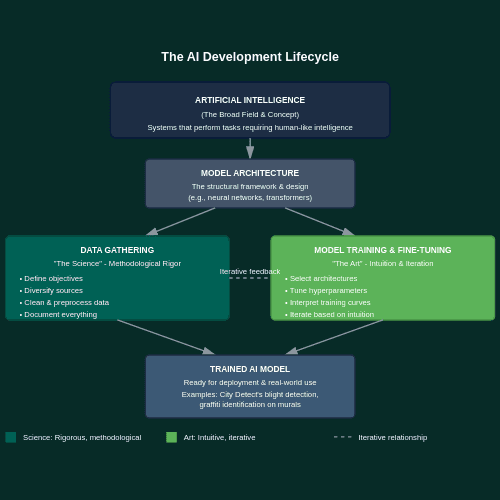

The prevailing narrative frames artificial intelligence as an engineering discipline: systematic, reproducible, governed by algorithms. This framing holds merit during certain phases of the AI model development lifecycle, yet it obscures a more nuanced reality.

While the data gathering phase must follow strict protocols, the training phase is considerably more enigmatic. This article explores the dual nature of AI model development: the science and the art. While data acquisition demands methodological rigor akin to laboratory science, the training and fine-tuning of the model itself reveals an artistic, intuitive process, balancing human judgment and machine learning analogous to sculpture.

Think of a sculptor starting with a block of marble. The raw material must be high-quality, but the sculptor does not follow a formula to create art. They chip away, step back, and adjust. In much the same way, the AI practitioner must balance precision with intuition.

The Science: Building the Dataset Foundation

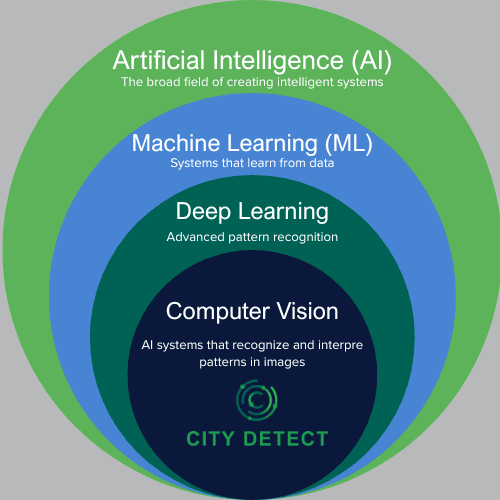

The data gathering phase demands scientific rigor for good reason. This is where scientific rigor is paramount, with well-established best-practice protocols to follow. The required precision varies by application. Computer vision models (AI systems that analyze and interpret visual information) demand meticulous attention to detail. A single mislabeled image can corrupt training, much like a teacher providing incorrect answers on a study guide.

At City Detect, we analyze imagery to identify dozens of indicators of urban blight and decay, including boarded windows, graffiti, overgrown lots, and damaged infrastructure. We proactively address regional variations through a methodical calibration period that centers on partnership and communication. Working closely with municipal teams to understand their priorities and local context, we iteratively refine our models to reflect each community's ground truth.

Photo Source: Backyard City

In Henderson, Nevada, for example, our model initially labeled window shades as plywood boarding. The model had been trained primarily on Southeast data, where plywood boarding is common due to hurricanes, but sun shades are rare. As a native Floridian, the difference was subtle at first. However, through our initial calibration and data-gathering process, in conjunction with Henderson officials, we successfully refined the model for their specific environment and are able to distinguish between sun shades and plywood at near-human-level accuracy. This example of communication and local calibration is a perfect example of why human input, local partnerships, and dataset diversity matter.

An organized, pristine environment, free of inconsistencies and with clearly defined patterns, improves learning efficiency by making features more recognizable to the model. Here are the essential best practices we use at City Detect for rigorous & ethical data gathering:

Define before data collection. Teams must clearly specify the target problem before gathering a single data point. A teacher who hasn't defined their subject scope and learning outcomes will teach without focus, introducing noise (irrelevant content that confuses rather than clarifies). Properly defined objectives ensure that dataset features align with project goals.

Diversify data sources strategically. The strongest datasets draw from multiple sources, including internal collection systems, synthetic data generation, and, when feasible, open-source repositories. This multi-source approach helps reduce bias and improve the model's generalization to real-world scenarios. However, this only holds true when the resulting dataset resembles the inference population, the real-world data the model will encounter during deployment.

Clean with methodical precision. Data preprocessing isn't glamorous, but it is critical. This involves several key steps:

Remove duplicates to ensure each unique image appears only once in the dataset.

Handle missing values, such as incomplete metadata or corrupted image files

Address outliers by removing data that doesn't help the model learn accurate patterns. However, if a condition could occur during real-world use, include representative examples in training. At City Detect, our DCUs capture images in all weather conditions, including reduced visibility conditions like rain, fog, dawn, and dusk. So, clean training data reflects these real-world scenarios. (We also implement deployment-level quality checks that measure sharpness and filter out poor-quality images before analysis.) This ensures the model handles diverse conditions while clients receive results only from usable images.

Standardize formats by converting images to consistent file formats (like JPEG or PNG), resizing to uniform dimensions (such as 512x512 pixels), and ensuring color modes are standardized (RGB vs. grayscale)

Document everything. Track dataset origins and metadata from day one. This documentation trail ensures reproducibility and allows you to understand what the model has learned. If the model consistently underperforms on a given task, you must be able to identify whether it's because the training data was inconsistent or insufficient.

These practices align with established standards for dataset development created by AI researchers and practitioners: prioritize quality and diversity, ensure transparency through documentation, address bias systematically, and maintain ethical standards throughout the data lifecycle. For further reading, see below.

The Art: Sculpting the Model

Once the dataset is prepared, training the model becomes an exercise in intuition and iteration. The AI practitioner no longer follows a protocol but develops a feel for how the model is learning, making judgment calls about what needs adjustment, and bridging the gap between how machines learn and how humans understand.

Let’s return to that sculptor with a block of marble metaphor: With quality materials in hand (the rigorously prepared dataset), the sculptor doesn't follow a formula. They work through countless micro-decisions: chip away here, smooth there, step back to assess the emerging form. The difference between competent and exceptional sculpture isn't just in the material; it's in the sculptor's developed intuition for the craft.

This sculptor metaphor resonates particularly well with computer vision models like ours, where we’re refining the model's ability to recognize and categorize what it sees. Our graffiti detection model, for instance, can distinguish vandalism from murals and public art, a nuanced judgment that required countless refinements.

Model training embodies this artistic approach. The AI practitioner begins by selecting the medium, the model architecture (the fundamental structural framework that defines the network structure and determines what patterns it can recognize). Just as a sculptor chooses between clay's malleability and marble's permanence based on their vision, the AI engineer selects architectures based on the problem's demands. Then the AI engineer configures the technique by tuning hyperparameters: the settings that control how the model learns, like learning rate and batch size. This is analogous to the sculptor choosing chisel size, angle of approach, and how aggressively or delicately to hammer. These technical decisions profoundly affect the outcome. Beyond these technical choices, the engineer is also:

Reading between the lines of training curves, developing intuition about whether a performance plateau means more data is needed, refining what the model looks for in each image, or a fundamental architecture change.

Translating between machine and human understanding, interpreting what the model is learning, and whether it aligns with meaningful patterns or just memorizes irrelevant correlations.

Iterating based on feel, knowing when to push through apparent failures and when to abandon an approach entirely.

The model provides metrics like loss functions (mathematical measures of prediction error), accuracy scores, and F1 scores that balance precision and recall. These metrics help quantify training performance, but they don't fully capture the nuanced judgment calls required during training. The engineer provides the meaning behind these numbers and decides what "good enough" looks like. This includes recognizing when the model has learned something genuine versus when it's exploiting misleading patterns in the dataset.

While it's true that AI excels at capturing and analyzing countless decisions, there's a critical distinction between inference and training: AI can execute micro-decisions based on learned patterns, but determining which architectural choices, training strategies, and trade-offs will solve a novel problem requires nuance and big-picture intuition.

Where Science and Art Meet

The interplay between the scientific rigor of data preparation and the artistry of the training matters because neither stage alone produces a robust AI model.

Scientific rigor in data gathering provides users with a foundation they can trust. No amount of artistic intuition can overcome a biased, incomplete, or poorly documented dataset.

Artistic intuition in model training brings essential human judgment to the training process. Without this sculptor's sensibility, the AI engineer simply replicates without understanding why they work or when they fail. Without the artistic intuition, the engineer struggles to diagnose problems, recognize opportunities, or refine architectures to solve novel challenges. They can chip away at the marble, but they can't create something genuinely innovative or impactful.

This matters especially when applying technology to longstanding problems. Blight detection isn't new, but applying computer vision at scale across diverse urban environments, including desert cities and humid regions, varied building styles, and seasonal changes, requires both custom-built model architectures and continuous calibration on relevant data points. Standard, off-the-shelf approaches can't handle the breadth of indicators simultaneously while adapting to regional variations and municipal priorities. Novel applications of proven technology to complex, real-world problems demand the AI practitioner to move fluidly between scientific rigor and artistic intuition.

The best AI practitioners embody this balance. They're meticulous about data provenance and preprocessing. They split the datasets properly into training, validation, and test sets.

And then they get creative. They experiment. They develop hunches. I've found that this playful curiosity, the willingness to try unconventional approaches, defines the artistic dimension. Practitioners learn to sense when a model is struggling versus when it's on the verge of a breakthrough. They become translators between the precise, literal world of computation and the nuanced, context-dependent world of human intelligence.

Conclusion

Acknowledging this dual nature isn't merely philosophical; it's practical. Teams that treat both data acquisition and model training as pure engineering will inevitably plateau. Those who embrace the artistic dimension, developing intuition through experience, find themselves better equipped to navigate the entire AI lifecycle.

At City Detect, this balance allows us to deliver reliable urban analytics across vastly different environments. Whether we're identifying abandoned vehicles in Stockton, CA, shopping carts in Henderson, NV, or snipe signs in Columbia, SC, the combination of scientific rigor and artistic refinement ensures our models serve the communities that depend on them.

If you're exploring how computer vision and AI can transform your city's operations, I'd welcome a conversation about how these principles apply to your specific context. Schedule a call with our team to discuss how we can help you navigate both the science and art of urban analytics.

Key Terms

Computer Vision: AI systems that analyze and interpret visual information from images or video.

Hyperparameters: Configuration settings that control how a model learns, distinct from the patterns the model actually learns from data.

Inference Population: The real-world data and conditions the model will encounter during deployment.

Loss Functions: Mathematical measures of prediction error that help quantify how well a model is performing during training.

Model Architecture: The fundamental structural approach and design of an AI system (e.g., neural networks designed for images versus sequential data).

Neural Networks: Computational systems modeled after the human brain's structure, designed to recognize patterns in data.

Noise: Inconsistencies or irrelevant variations in data that can confuse model training.

Outliers: Statistically anomalous data points that don't represent true patterns in your dataset. Requires careful judgment to distinguish between true outliers (to remove) and legitimate regional variations (to include).

Transformer Architectures: Advanced AI models that excel at identifying patterns and relationships in data, particularly effective for processing sequential information.

Further Reading

For those interested in diving deeper into AI dataset best practices, see work by Chris Emura, D. Zha, Steven Euijong Whang, Yuji Roh, Tiffany Tseng, K. Drukker, William Cai, Amandalynne Paullada, and Ben Hutchinson.

We're always excited to connect with fellow practitioners pushing this field forward. Connect with us on LinkedIn.

Ready to Change Your Community?

Ready to Change Your Community?